Robert

Bike

Licensed

Massage Therapy #5473

Eugene, Oregon

EFT-CC, EFT-ADV

Teaching Reiki Master

Life Coach

Gift Certificates

|

Reiki

Private classes. |

|

Member

OMTA & ABMP President of the Oregon Massage Therapists Association 2008-2010 & 2012-2013 |

|

I

graduated from Freeport (Illinois) High School. |

|

Please

help keep

this site free. Buy one of my books, on sale below. All sales go to help support this website. |

|

Remarkable

Stories, Remarkable

events have happened in Freeport and Stephenson County, Illinois,

and remarkable people have lived there. These are stories

gathered about people and events from 1835 through World War

II. |

|

Biblical

Aromatherapy

by Robert Bike

The Bible mentions about 232 plants by name, or closely enough to figure out what plant is meant. Of these, 24 are aromatic plants; that is, parts of the plants can be pressed or distilled to get an essential oil. Essential oils are the lifeblood of plants and have tremendous healing capabilities. The

healing power of plants is the basis for modern medicines.

Originally published in manuscript form in 1999, I completely revised the book and added illustrations. To

order Biblical Aromatherapy in paperback, List price $24.99; introductory offer $19.99 To order the pdf version and download to your computer or phone, The electronic version is only $2.99! |

Publicity!

|

Olga

Carlile, columnist for the Freeport (Illinois) Journal Standard,

featured this website in her column on January 19, 2007. |

|

Harriet

Gustason, another columnist for the Freeport Journal Standard,

has featured this website twice. Click to see pdf of articles:

June 29, 2012 November 3, 2012 |

|

"My

Life Purpose is to inspire my friends |

Robert Bike, LMT, LLC

The Class of 1850

While FHS was not yet on the graded system with classes, there were students attending.

The Freeport High School Official Seal shows that the school was founded in 1850. The seal was shown on the cover of the 1966 Polaris.

I'm still researching early Freeport High School history. Information about all Freeport students before the first class will be included with the Class of 1850.

William

"Tutty" Baker

While

we generally think of Freeport in terms of the white settlers and the

community they founded in the mid-1830s, there was actually a Native American

village located where the old Illinois Central passenger station was,

on the west bank of the Pecatonica, just south of the Stephenson Street

bridge. The village was called Winneshiek, and the chief of the village

was also named Winneshiek, which means Coming Thunder.

While

we generally think of Freeport in terms of the white settlers and the

community they founded in the mid-1830s, there was actually a Native American

village located where the old Illinois Central passenger station was,

on the west bank of the Pecatonica, just south of the Stephenson Street

bridge. The village was called Winneshiek, and the chief of the village

was also named Winneshiek, which means Coming Thunder.

This was a fine location for the local band of Winnebagoes. The Pecatonica River provided water and food in the form of fish and turtles. There was fertile land to grow their crops. And large herds of buffalo and deer ran through the prairies and woods. Food was plentiful, and life was good until the white men came.

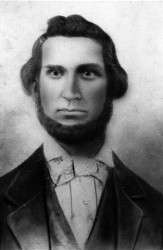

On

the 24th of December of 1835, William "Tutty" Baker (left, as a young

man, right as an old man) settled permanently about a half mile upstream

(northwest) of this spot, near what we call the Van Buren Street Bridge.

He claimed 640 acres of land, and plotted out streets and lots for building.

He called his village Winneshiek, after the Indian village. He was a generous

man, and helped many people settle here. There were no bridges, and few

ferries. As the westward traveling settlers passed through, he used his

canoe and his hospitality to help all.

On

the 24th of December of 1835, William "Tutty" Baker (left, as a young

man, right as an old man) settled permanently about a half mile upstream

(northwest) of this spot, near what we call the Van Buren Street Bridge.

He claimed 640 acres of land, and plotted out streets and lots for building.

He called his village Winneshiek, after the Indian village. He was a generous

man, and helped many people settle here. There were no bridges, and few

ferries. As the westward traveling settlers passed through, he used his

canoe and his hospitality to help all.

Baker established an Indian trading post and a tavern. He would travel in his canoe to distant settlements, including going as far as Peoria, to get supplies, and row back upstream with what he needed for his family and his customers.

In

the spring of 1836, Baker brought his family to the land he had claimed.

Elizabeth Phoebe Baker was the first white woman to see the area. Caroline

Baker (shown at left) was the third white child born in Winneshiek, on

May 28, 1838; she later married Amos Doane and moved to Kansas. Rivers

John Fowler was the first white child, born on August 31, 1837; Sarah

Jane Hollenbeck was the second, born on December 15, 1837; Joseph John

Earle was born March 10, 1839. Other babies may have been born earlier,

but these four survived infancy.

In

the spring of 1836, Baker brought his family to the land he had claimed.

Elizabeth Phoebe Baker was the first white woman to see the area. Caroline

Baker (shown at left) was the third white child born in Winneshiek, on

May 28, 1838; she later married Amos Doane and moved to Kansas. Rivers

John Fowler was the first white child, born on August 31, 1837; Sarah

Jane Hollenbeck was the second, born on December 15, 1837; Joseph John

Earle was born March 10, 1839. Other babies may have been born earlier,

but these four survived infancy.

L.

O. Crocker arrived in 1836 and built a store, located at the east end

of Main Street, on the west bank of the Pecatonica.

L.

O. Crocker arrived in 1836 and built a store, located at the east end

of Main Street, on the west bank of the Pecatonica.

By 1837 Baker had also built a rudimentary hotel. The tavern on the riverbank, which was also the Baker home, was the gathering place in the village of Winneshiek. Baker, as mentioned previously, was exceedingly generous. One morning, after he had given away food and hospitality to yet another traveler, Phoebe Baker (right) sarcastically suggested that instead of Winneshiek, the village should be called Freeport, because Tutty gave everything away for free. Tutty laughed, and told the story to all the other settlers, and soon the village was called Freeport.

So, if you were born or raised in Freeport, and your momma sasses you for your sarcastic sense of humor, just explain to her that you come by it naturally, because your home town is named after a sarcastic joke!

Black

Abe, Abram Follock

Black Abe was employed by "Father" Brewster and wanted an education. John

K. Brewster had settled in Oneco in 1838, then moved to Freeport. He later

built the Brewster House Hotel.

There was some dissent about 16-year-old Black Abe attending school in the winter of 1845-1846 and sharing a desk with a white boy because there was tremendous prejudice at the time, but Mr. Sunderland convinced all that it was in everyone's best interest that Black Abe be allowed to attend school. Black Abe remained a scholar at Freeport School, but I don't have a record of Black Abe graduating from Freeport High School. The first black that I have confirmed to be an FHS graduate was George Lipscomb in 1917.

Black Abe was listed in the 1850 census as Abram Follock, 21, a native of New York. He was a barber.

The first issue of Freeport's first newspaper, the Prairie Democrat, dated November 17, 1847, had an advertisement of Follock's Barber Shop. On January 24, 1849, he advertised, "A. A. Follock, Knight of the lather and brush, holds forth at his barber shop at the Stephenson County Hotel, in Freeport, Illinois, where he will be ready to wait upon his customers at all hours. Shaving, Hairdressing and Shampooing done in the latest and best approved style and fashions of 1848-49."

He advertised that he went to ladies' homes to shampoo their hair. At his shop, he sold hair oil, perfumery, razors, hair brushes, combs and scissors. His prices were: Shaving - 6-1/4 cents, hair-cutting - 12-1/2 cents. His barber chair is now at the Stephenson County Museum.

Alexander

Cameron Hunt

A.

C. Hunt was born in Hammondsport, New York, on January 12, 1825. His father,

Richard Hunt, brought the family to Freeport, arriving in the spring or

summer of 1837. In the fall of 1837, Richard erected a frame building

at Galena and Van Buren Streets, where he set up his office of Justice

of the Peace, and a second building on the corner of Van Buren and Spring

Streets. His two daughters, Eliza and Sarah attracted the attention of

all the young men.

A.

C. Hunt was born in Hammondsport, New York, on January 12, 1825. His father,

Richard Hunt, brought the family to Freeport, arriving in the spring or

summer of 1837. In the fall of 1837, Richard erected a frame building

at Galena and Van Buren Streets, where he set up his office of Justice

of the Peace, and a second building on the corner of Van Buren and Spring

Streets. His two daughters, Eliza and Sarah attracted the attention of

all the young men.

Boys at that time often learned the trade of their fathers, but Richard was a Justice of the Peace, so A. C. learned other things. His mother and older sisters taught him to cook. He helped his father and others in the new community of Freeport build the first homes and business. And he played with the other boys in the community, including probably the Native American boys in the nearby village. The Baker children could speak the language of the natives, and A. C. probably learned some of the language as well. All these skills would serve him well in the rest of his life.

When Nelson Martin opened the first school in Freeport in the fall of 1837, 12-year-old A. C., Eliza, Sarah and Hamilton Hunt were among the first students.

When

gold was discovered in California in 1849, A. C. went west seeking gold

with one of the Baker boys and several other Freeporters. Apparently he

did well. When he returned, A. C. became a successful Freeport businessman.

The 1856 City Directory listed an ad for Brewster & Hunt, Forwarding

& Commission Merchants and general dealers in produce and grain. The

owners were listed as J. K. Brewster and A. C. Hunt. As you will see,

A. C. often got involved with several businesses at one time. I suspect

he also ran a restaurant, and that A. C. was the cook.

In 1851, 26-year-old Cameron Hunt married 17-year old Ellen Elizabeth Kellogg.

In 1856, A. Cameron Hunt was elected the second mayor of Freeport. In 1857 he was elected to his second one year term.

There was a depression that struck the country in 1857, and Cam Hunt lost his businesses.

In 1858 A. C. heard that gold had been discovered in Colorado at Pike's Peak. So in the spring of 1859, he took his wife Ellen, daughter Isa, son Albert (Bertie), and his father Richard, and headed west.

At

Kansas City they joined a wagon train headed for Pikes Peak. At Cimarron

Crossing, a St. Louis couple decided to take the cutoff to Santa Fe. Two

days later, Mr. Walsh and son called for a division of common property

so that they might return home. The pair received as their share one wagon,

a yoke of cattle, cows, sheep, a pony and some chickens as well as their

own personal supplies. The remainder of the company kept on towards the

mountains, bound by a mutual agreement to continue on to California if

Pike's Peak was not satisfactory. “I dread the long journey, oh

I do,” Ellen Hunt wrote in her diary, “but when we stop again

I want to stay, and never move again, and shall not go on, till we are

satisfied.” Of the 150,000 who started for the gold fields, at least

50,000 turned back. Some wrote "Pikes Peak or bust" on their wagons, and

many busted out or died along the way.

At

Kansas City they joined a wagon train headed for Pikes Peak. At Cimarron

Crossing, a St. Louis couple decided to take the cutoff to Santa Fe. Two

days later, Mr. Walsh and son called for a division of common property

so that they might return home. The pair received as their share one wagon,

a yoke of cattle, cows, sheep, a pony and some chickens as well as their

own personal supplies. The remainder of the company kept on towards the

mountains, bound by a mutual agreement to continue on to California if

Pike's Peak was not satisfactory. “I dread the long journey, oh

I do,” Ellen Hunt wrote in her diary, “but when we stop again

I want to stay, and never move again, and shall not go on, till we are

satisfied.” Of the 150,000 who started for the gold fields, at least

50,000 turned back. Some wrote "Pikes Peak or bust" on their wagons, and

many busted out or died along the way.

Ellen was sick from the start. Large purple blotches formed on her body, which Richard called erysipalis, an acute bacterial infection of the skin. It confined her inside the wagon most of the way. By the time the party turned onto the Cherokee Trail, Ellen was feeling better. As they headed up Fountain Creek, her spirits began to soar; when the party reached Jimmy Camp, she was ready to homestead.

The entry in Ellen's diary for June 24, 1859, reads, "Had a splendid view of the mountains for several miles. Begin to see finer country. Passed one fine location for a farm, beautiful prairies on a soil much like Pigeon Prairie, with grove of pine convenient. Camped near one and beside an elegant spring."

On

June 25, 1859, Ellen wrote, "Started at moon rise and traveled 15 miles

before breakfast, to a pine forest—very beautiful but sad from the

number of graves here—8 are in view of persons who have frozen to

death, one as late as June third, '59. The changes are so sudden even

in the summer that from being very warm it will be so cold as to benumb

the body before fire can be made to warm it. These changes generally occur

after a rain, or storm of some kind." At left, Fagan's Grave, one of the

graves Ellen Kellogg Hunt saw on June 25, 1859

On

June 25, 1859, Ellen wrote, "Started at moon rise and traveled 15 miles

before breakfast, to a pine forest—very beautiful but sad from the

number of graves here—8 are in view of persons who have frozen to

death, one as late as June third, '59. The changes are so sudden even

in the summer that from being very warm it will be so cold as to benumb

the body before fire can be made to warm it. These changes generally occur

after a rain, or storm of some kind." At left, Fagan's Grave, one of the

graves Ellen Kellogg Hunt saw on June 25, 1859

Her

June 26, 1859, entry reads, "Started again before day, traveled till nine,

breakfasted and were off again at 11 1/2oc. Sand very deep, soil looks

poor. No trees save a few cottonwoods along Cherry Creek. Camp at 7 oc

in a better looking country, 5 miles from Denver, in a rain storm which

continued until nine oc." (At right, Cherry Creek.)

Her

June 26, 1859, entry reads, "Started again before day, traveled till nine,

breakfasted and were off again at 11 1/2oc. Sand very deep, soil looks

poor. No trees save a few cottonwoods along Cherry Creek. Camp at 7 oc

in a better looking country, 5 miles from Denver, in a rain storm which

continued until nine oc." (At right, Cherry Creek.)

On June

27, 1859, Ellen wrote in her diary, "Monday - 27th. Started at 7 1/2 oc.

The day was intensely hot and roads dusty. Traveled slow and arrived at

D [Denver] 20 minutes before 11. The cabin Ham had engaged was on the

very outskirts of Auraria, built of logs and mud, with neither windows

or floor. 'Tis much better than most of its neighbors but at first I felt

blue enough at the prospect of even trying to live in such a place. When

once at work trying to make it comfortable I felt better. A partition

was made of our wagon cover, shelves here and there. I sleep comfortable

all night notwithstanding my fear of the Indians, of which about 300 are

here.”

They

settled in the Cherry Creek area, which is now a part of Denver. The mouth

of Cherry Creek was a site of gold digging.

They

settled in the Cherry Creek area, which is now a part of Denver. The mouth

of Cherry Creek was a site of gold digging.

A. C. built a log cabin and opened a restaurant. Thieves and crooks ruled the territory, so he organized his neighbors and was elected judge of the vigilante committee, which cleared the undesirables from the community by capturing, trying and hanging the offenders.

Hunt was also in the livery business with John M. Clark, at 3rd Street, Auraria. He also was president of the Capitol Hydraulic Company of Auraria, which constructed ditches for irrigation. By the end of 1859 he was Vice President of Auraria Town Company, and in March 1860 he presided over a meeting which united Auraria with the smaller village across the creek, Denver City. The combined town was named Denver.

On

June 10, 1862, Abraham Lincoln appointed A. C. Hunt to be United States

Marshall, a position he held for five years. He was also appointed Ex-Officio

Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

On

June 10, 1862, Abraham Lincoln appointed A. C. Hunt to be United States

Marshall, a position he held for five years. He was also appointed Ex-Officio

Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

A. C. Hunt built the first brick house in Denver.

During the administration of Alexander Cummings, the third governor of Colorado from 1865-1867, Hunt served for a time as Treasurer of Colorado Territory.

In 1867, A. C. ran for congress. There was considerable voter fraud in the election. His opponent was elected, but A. C. was rewarded with the appointment of Governor of the Colorado Territory on April 24, 1867. Portrait at right is Governor Hunt.

Shortly

after his appointment to the governorship he and Colorado's First Lady,

Ellen Kellogg Hunt, made a six week trip through Colorado. At one party

where Vice President Schuyler Colfax (photo at left) was the guest of

honor, the cook had ruined the meal. Hunt took upon himself the duty of

chef. Ellen protested. She didn't think it was proper for a governor to

cook for the Vice President of the United States. But Hunt was proud of

his cooking abilities.

Shortly

after his appointment to the governorship he and Colorado's First Lady,

Ellen Kellogg Hunt, made a six week trip through Colorado. At one party

where Vice President Schuyler Colfax (photo at left) was the guest of

honor, the cook had ruined the meal. Hunt took upon himself the duty of

chef. Ellen protested. She didn't think it was proper for a governor to

cook for the Vice President of the United States. But Hunt was proud of

his cooking abilities.

His administration was dominated by conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans. Because he had been Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and continued to hold that position, he had excellent relations with the natives.

In February of 1868, A. C. got the Ute Chiefs, Indian agents and President Andrew Johnson together to discuss a treaty. Because of A. C.'s good relations with the Indians, a treaty was signed. The federal government, of course, reneged on the agreement, which angered the Indians. A. C. personally rode from one Indian encampment to the next and to the next to defuse the situation. He went to the camps alone and unarmed.

He remained governor until June 14, 1869.

After

he was out of office, A. C. continued to work to develop Colorado. He

was the pathfinder and builder of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad (photo

at right). Hunt conceived taking narrow-gauge tracks across nearly unbridgeable

chasms and snow-covered passes of the Rockies. He would ride 100 miles

a day on horseback while supervising the work. He opened six of the leading

mines of Colorado.

After

he was out of office, A. C. continued to work to develop Colorado. He

was the pathfinder and builder of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad (photo

at right). Hunt conceived taking narrow-gauge tracks across nearly unbridgeable

chasms and snow-covered passes of the Rockies. He would ride 100 miles

a day on horseback while supervising the work. He opened six of the leading

mines of Colorado.

Hunt helped to develop the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

Hunt is credited with introducing the first bee colony to Denver.

Hunt pioneered the use of alfalfa in Weld County.

At a dinner party one night, Ellen noticed that A. C. wasn't saying much. She asked him to engage in conversation with the guests. He replied that he doesn't talk, he takes action. If she could find something for him to do, he'll do it! And that little story sums up his life. He was a doer, and he got a lot done.

As

president of the Rio Grande railroad, Hunt went to Mexico to obtain concessions

to build the Mexican National Railroad from Laredo to Mexico City. He

and 12,000 employees built a narrow-gauge line two thousand miles, connecting

the capital of Mexico with Texas.

As

president of the Rio Grande railroad, Hunt went to Mexico to obtain concessions

to build the Mexican National Railroad from Laredo to Mexico City. He

and 12,000 employees built a narrow-gauge line two thousand miles, connecting

the capital of Mexico with Texas.

Hunt opened the San Tomas mine west of Laredo and constructed a private railroad to move his coal to market. This was the Pecos Railroad. It ran 26 miles along the Rio Grande. He had large property interests in Texas and Mexico.

Hunt established the first electric light plant at Laredo, Texas, and put up wires across the Rio Grande to electrify Nuevo Laredo, Mexico.

In 1891, while in Chicago, he had a stroke, and he only partially recovered.

Alexander Cameron Hunt died in May 1894 at his residence in Tenleytown (a historic neighborhood in northwest Washington, D. C.), and is buried at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington. He was the father of Isa, Albert, Robert, and two children who died in infancy, Isabel and Bruce. Ellen died August 8, 1880. He married Alice Underwood on June 3, 1889. They had a daughter, Gloria. Gloria died in 1918, Alice in 1920.

On

February 23, 1908, a granite boulder was shipped from Colorado to Washington

to mark the last resting place of Alexander Cameron Hunt. The stone was

the gift of General William J. Palmer, A. C.'s former business partner,

a Civil War general and founder of Colorado Springs (portrait at right).

The boulder is red granite, taken from the Ute Pass, weighs several tons,

and when placed in the Congressional Cemetery was the only monument of

its kind.

On

February 23, 1908, a granite boulder was shipped from Colorado to Washington

to mark the last resting place of Alexander Cameron Hunt. The stone was

the gift of General William J. Palmer, A. C.'s former business partner,

a Civil War general and founder of Colorado Springs (portrait at right).

The boulder is red granite, taken from the Ute Pass, weighs several tons,

and when placed in the Congressional Cemetery was the only monument of

its kind.

In this

cemetery, endowed by Congress, Governor Hunt lies in the lot of United

States District Judge of Virginia John C. Underwood and Mrs. Underwood,

parents of the second Mrs. Hunt. An inscription on the family monument

states, "Alexander Cameron Hunt of Colorado Crossed the Divide May 14,

1894."

The Remarkable Manny Family

People

mentioned in this story:

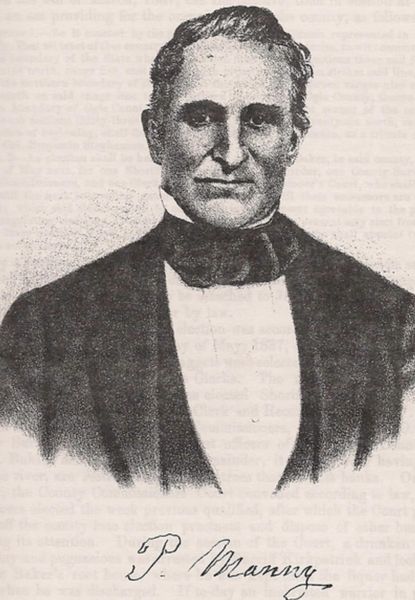

Pells Manny (1802-1883) - McConnell farmer, inventor

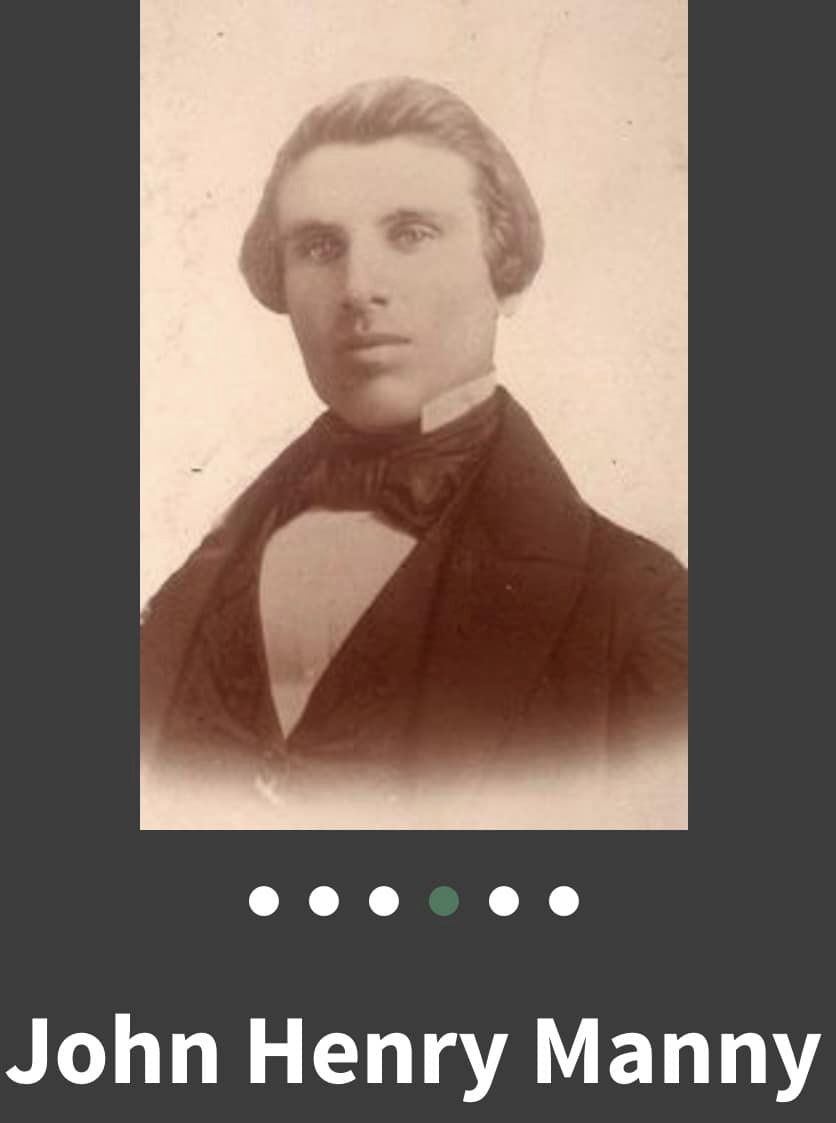

John Henry Manny (1825-1856) - son of Pells, inventor

Mary Dorr Manny (1827-1901) - wife of John Henry Manny

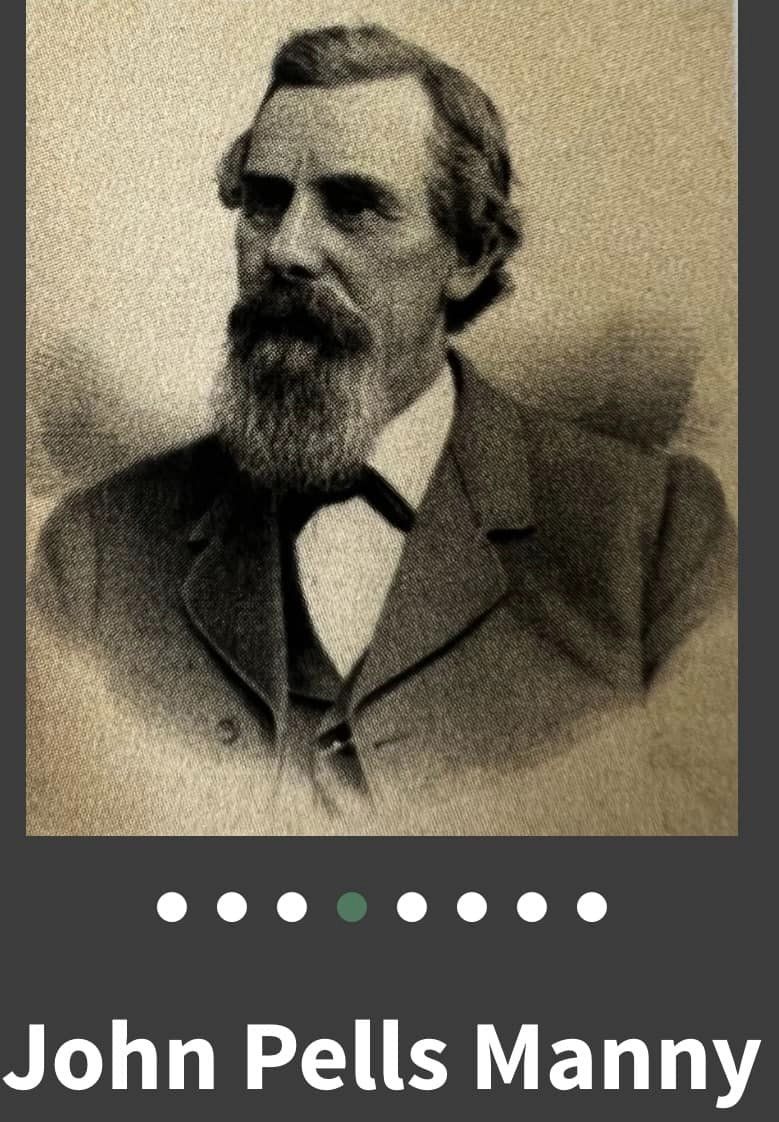

John Pells Manny (1823-1897) - nephew of Pells, blacksmith, inventor

Frederick Henry Manny (1818-1899) - son of Pells, businessman, inventor

Eliza Manny (1829-1905) - daughter of Pells

Jeremiah Pattison (1820-1895) - owned general store in Waddams Grove,

married Eliza, businessman

George Esterly (1809-1893) - Wisconsin inventor

Ralph Emerson (1831-1914) - Rockford hardware store owner, businessman,

philanthropist

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) - philosopher

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) - attorney, president

Cyrus McCormick (1809-1884) - Chicago businessman

Jo Anderson (1808-1888+) - inventor, slave on McCormick plantation in

Virginia

Edwin Stanton (1815-1869) - attorney, Secretary of War

Robert Hall Tinker (1836-1924) - Accountant for J. H. Manny and Company

Napoleon III (1808-1873) - President and Emperor of France

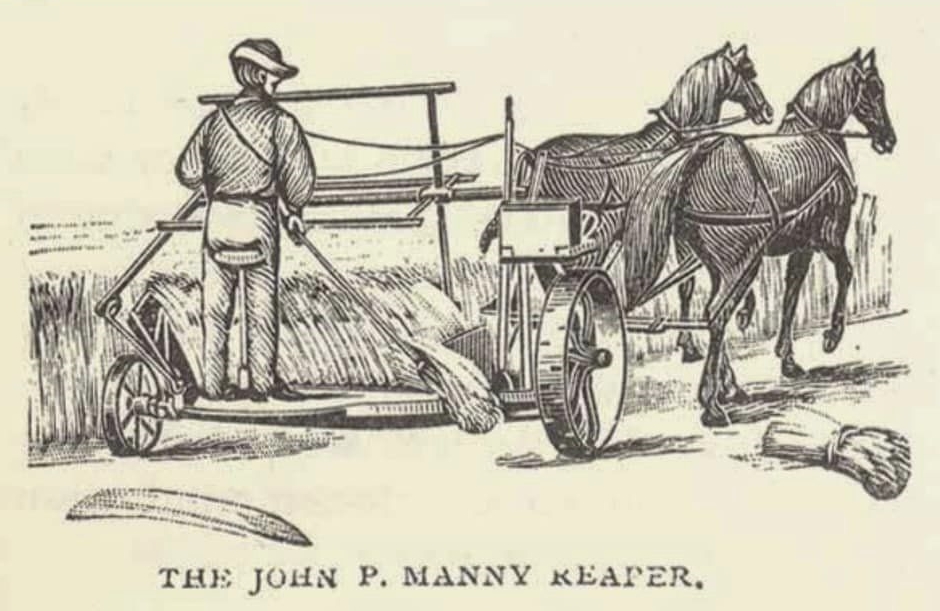

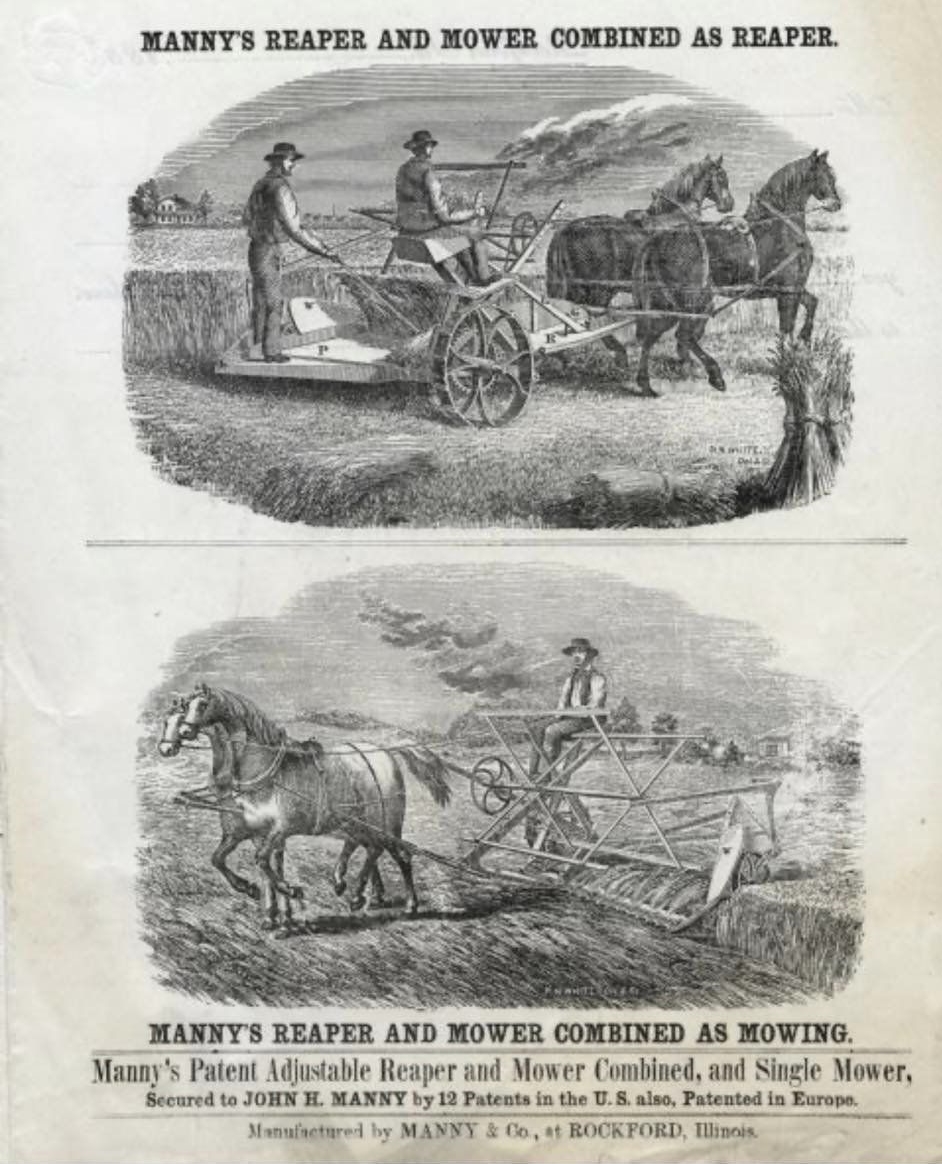

Farmers in Stephenson County in the 1840s and 1850s grew corn, oats and

hay for their food and animal feed, but they grew wheat as a cash crop

because cities needed wheat flour for bread. There was a narrow window

of 1-2 weeks in the fall for harvesting wheat, and one person with a scythe

could cut only three acres per day, maximum. Farmers used family, day

laborers and neighboring farmers for help during the brief harvest period.

Several people around the world were building mechanical reapers to harvest

wheat, but the machines were cumbersome, individually hand-built, expensive,

and often didn’t work well. In 1848, Pells Manny and his son John

Henry Manny (JH) heard about a Whitewater Wisconsin inventor who was building

a reaper, so they went to try to buy one.

George Esterly built his first reaper in 1844 and was building an improved

reaper in 1848, but couldn’t get the cutting parts of it to work

properly, and would not have one finished in time to sell to Pells for

that year’s harvest, so JH stayed on to help him and learn how it

was supposed to work while Pells returned home.

Pells went back to farm work, but in his spare time began building his

own reaper. When JH returned home, they completed their first reaper.

It was huge, required eight horses to operate, and the cutting blades

rapidly dulled. But when it worked, one man could use the reaper to harvest

17 acres of wheat in a day!

They turned to Pells’ nephew, John Pells Manny (JP), who was a blacksmith,

to help them solve the problem of the rapidly-dulling blades. At this

time in history steel was hardened by heating it in a forge, pounding

it with a hammer, dipping the steel into salt brine to cool it, and repeating

the process multiple times. JP came up with a secret process that used

an oil solution for cooling. His steel was harder and his blades stayed

sharp significantly longer.

Pells, JH and JP continued to refine their reaper, making it smaller and

more efficient. Pells got his first patent in 1849. All three got multiple

patents over the next several years as they continued to develop a reaper

that would be easy to manufacture and reliable to operate.

Pells, JH and JP continued to work on improvements, selling a few reapers

every year while investing tens of thousands of dollars. They started

a small factory on Waddams Creek, just across the road from Pells’

farm about a mile southwest of McConnell, using a water wheel to power

their machinery. In 1852 they built 84 reapers and sold them for $135

each. Calculating for inflation, $135 in 1852 is about $3500 in 2023.

So 84 reapers in today’s money is almost $300,000!

Though they built and sold 84 reapers, their problem was that they had

hundreds of orders!

Using knowledge gained from the blades used in the reaper, they added

a mower to their product line. They demonstrated their machines at the

1852 New York State Fair, and the Manny Mower won first prize while the

Manny Reaper won second prize!

In 1853 they could only manufacture 150 machines, and they knew that they

had to have a bigger factory where they had access to a rail line to move

in raw materials and ship out finished products. They also needed access

to a larger workforce. And they were going to need funding.

They had been purchasing some of the hardware for their machines at a

hardware store in Rockford and JH mentioned to the proprietor that they

needed funding for a new factory.

Ralph Emerson had been studying law, but his good friend, attorney Abraham

Lincoln, suggested that Ralph go into business instead, so in 1852 at

age 21 Ralph borrowed money from his father, and with a partner, opened

a hardware store in Rockford. Ralph, whose first cousin was the great

American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, had many wealthy customers,

and he brought together a coalition of investors to build a reaper factory,

with the provision that it be built in Rockford.

The Rockford-based J. H. Manny and Company quickly grew to a workforce

of nearly 700, about 10% of Rockford’s population of 6700. In 1854

they sold 1100 reapers. In 1855 they sold 2900 reapers worth about 10

million dollars in 2023 money.

JP built his own factory supplying the cutting blades for the Manny Reaper

and other Manny machines.

It’s unclear what role Pells had in the Rockford company, but he

owned several patents, so he made money on every reaper sold.

Chicago’s Cyrus McCormick was losing business to Rockford’s

J. H. Manny and Company factory, so in 1856 he sued for copyright infringement.

His father had built an early reaper on his Virginia plantation with assistance

from their slave, Jo Anderson (some people believe that Anderson was the

real genius behind the McCormick reaper). Cyrus McCormick was not an inventor

himself, but he was an excellent marketer.

Manny and Company hired a couple of powerful east coast lawyers to defend

their patents, but they needed a local attorney to sit with them because

they were not licensed in Illinois. Ralph Emerson asked his friend, attorney

Abraham Lincoln, to be the local attorney representing Manny and Company

in defending the lawsuit.

McCormick, ever the shrewd businessman, somehow got the trial transferred

to Cincinnati, so the powerful attorneys didn’t need Lincoln. But

Emerson had hired him, so Lincoln went to Cincinnati. When Lincoln got

to the courthouse wearing his best suit, Edwin Stanton saw Lincoln and

asked, “Where did this long-armed baboon come from?” He described

Lincoln as “a long, lanky creature from Illinois, wearing a dirty

linen duster for a coat and on the back of which perspiration had splotched

white stains that resembled a map of the continent.” He prevented

Lincoln from taking any part in the defense and made him sit in the audience.

After that snubbing Lincoln was determined to become a better attorney,

speaker and debater. (Five years later after Lincoln was elected president,

he named Stanton to his cabinet as Secretary of War. Stanton became one

of Lincoln’s staunchest supporters. When Lincoln was assassinated,

Stanton famously said, “Now he belongs to the ages.”)

The lawsuit was closely followed by newspapers across the country. McCormick

lost the case and all the appeals. Emerson honored his commitment to Lincoln

and paid him well for his time and his research. Lincoln later said that

the thousands of dollars he was paid in fees by Manny and Company enabled

him to run for the Senate in 1858.

John Henry Manny died of consumption (tuberculosis) at age 30 two weeks

after winning the case. After JH’s death, Ralph Emerson stepped up

to lead the company, but the creative genius was gone. The company changed

names several times, first as Talcott, Emerson and Company, then in 1860,

Emerson and Company, in 1895 Emerson Mfg. Co., in 1909 Emerson-Brantingham,

and finally in 1928 J. I. Case of Racine Wisconsin bought the company

with all its patents.

John Henry Manny left behind a young wife and child. In 1870 his wife,

Mary Dorr Manny, married Robert Hall Tinker, the accountant for J. H.

Manny and Company. Their home and garden is now the Tinker Swiss Cottage

Museum in Rockford.

With JH dying in 1856, Pells and JP sought funding to open a factory in

Freeport.

In 1849 Pells’ daughter Eliza had married store owner Jeremiah Pattison

(Jere). He was a successful businessman and got together with Pells and

JP to develop a factory in Freeport. They began operations in 1856, and

moved into a new building on March 1, 1857.

Jere built Freeport’s first factory, a brick building on Liberty

Street, three stories high, 160x60, with room for 500 employees. The engine

room was a wing 60x30, and contained an 80 horsepower $6,000 engine to

drive the machinery. With a workforce of 400, Freeport’s Manny and

Company began building the Manny Reaper, the hand-raking and self-raking

reaper and mower, the Victory and the Advance walking wheel cultivators,

the Stover Champion riding cultivator, and the Freeport grain separator.

They built and sold tens of thousands of agricultural machines.

In 1858, Frederick Henry Manny, another son of Pells, came to Freeport

and got into the water power business. In 1860 he moved to Rockford and

began manufacturing the Manny Reaper and a fanning mill that separates

the grain from the chaff. Then he invented the Manny Seeder and a riding

corn cultivator. He built machines that made efficient use of water power.

He employed 200 workers and was the world’s largest manufacturer

of water-powered machines.

Pells Manny retired in 1863 because of poor health. Jeremiah Pattison

retired in 1876. Freeport’s Manny and Company continued to operate

until 1892, when the building was sold to the Tuckett Tobacco Company.

Guyer and Calkins used the building from 1901 to 1966 for wholesaling

groceries.

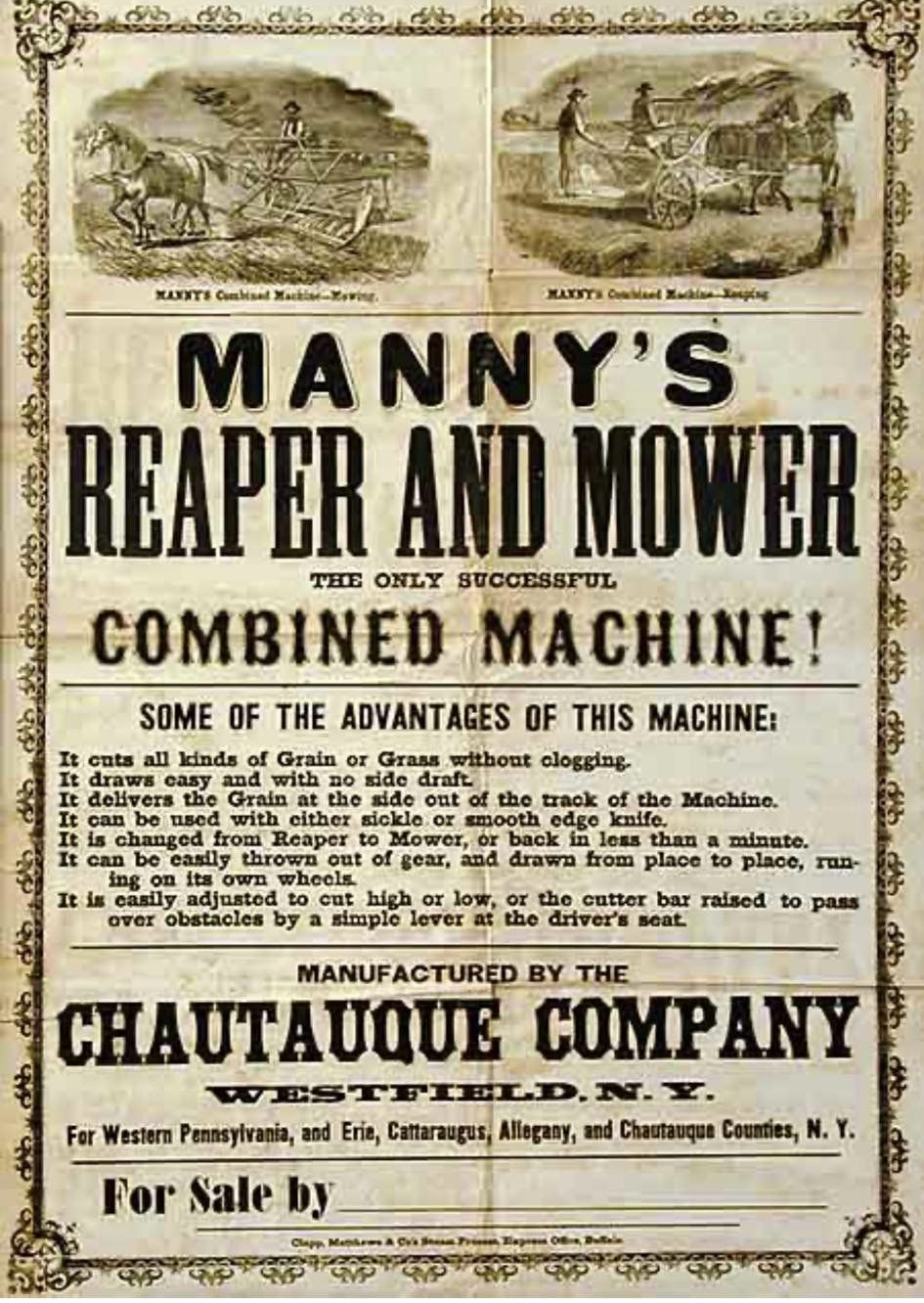

In the early 1860s, JP came up with some improvements and got a large

number of reaper patents. He was offered one million dollars for his formula

for hardening steel, but he turned down the offer; to this day his oil

process remains a secret. He contracted with The Chautauque Company of

Westfield, New York, to build Manny Reapers on the east coast. He invented

a machine to make lemon juice, which brought him even more wealth. In

1897 JP was president of a cemetery association, and worked alongside

the workers. They drank water from a contaminated well, and John Pells

Manny died from typhoid/dysentery. His Rockford home is now a wing of

the Burpee Museum of Natural History; many people have reported that the

house is haunted!

Ralph Emerson continued to invest in small businesses and contributed

to the development and success of 40 firms. Shortly after the Civil War

he was a central figure in the founding of the Emerson Institute in Mobile,

Alabama, for the purpose of educating newly freed slaves to teach them

vital skills like how to read and write. The school faced opposition from

the Ku Klux Klan, but operated until 1970.

The Manny Reaper was used in every U.S. state and in many countries around

the world. After winning first place at the Paris Exhibition of 1855,

Napoleon III, the President and Emperor of France, ordered two Manny Reapers!

George Esterly of Whitewater Wisconsin eventually made and sold the Esterly

Reaper in his own business by 1856, employing 500 workers.

Cyrus McCormick’s reaper company later became International Harvester/Navistar.

All the Manny inventors and entrepreneurs became incredibly wealthy.

There is so much more to the Manny story, but the real gem is that the

remarkable Manny family from McConnell Illinois transformed agriculture

from hand tools to machine tools with their inventions.

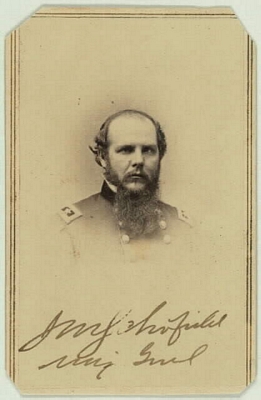

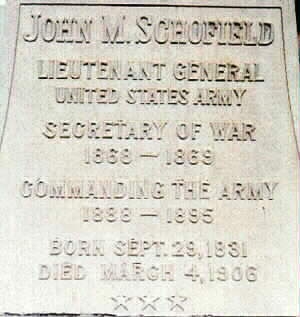

War

Hero, Medal of Honor winner, Secretary of War, Commander of the Army—can

you name this famous Freeporter?

War

Hero, Medal of Honor winner, Secretary of War, Commander of the Army—can

you name this famous Freeporter? John McAllister Schofield was born in Gerry, New York, on September 29, 1831, and at the age of 12 was taken by his father, the Reverend James Schofield, a Baptist minister, to Freeport, Illinois. Schofield always listed Freeport as his hometown.

His

mother was Caroline McAllister Schofield. James Schofield founded the

First Baptist Church in Freeport. In 1844, at the age of 13, John Schofield

was baptized by his father in the "Jordan of Illinois," the Pecatonica

River. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln appointed James

Schofield a Chaplain, where he spent his time ministering and writing

letters from dying soldiers to wives or mothers. Rev. James Schofield

had been an officer in the War of 1812 and the Schofield Family added

the "h" (Scofield to Schofield) to the name in 1844 when they moved to

Freeport.

Growing up, John Schofield excelled in education, sports and hard work on the family farm. At the age of 16 he spent several months doing surveying work in northern Wisconsin. At 17, he taught school in Oneco, Illinois. He decided on law as his chosen profession, and returned to Freeport to study Latin.

He attracted the attention of Freeport's Congressman, the U.S. Representative from Illinois' 6th District, Thomas J. Turner. When Turner's candidate for West Point cancelled at the last moment, he remembered a young man he saw teaching mathematics at his brother's school in Oneco, and appointed John Schofield to the West Point Military Academy. The Schofields sold some land and used their life's savings to get him there. Schofield later joked that if Turner had witnessed his class while he was teaching Latin that he never would have gotten the appointment.

On June 1, 1849, John McAllister Schofield arrived at West Point with less than two dollars in his pocket, at the age of seventeen years and nine months.

Schofield

graduated from West Point in 1853, seventh in his class.

He served for two years in the artillery. He served as Assistant Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy at West Point from 1855 to 1860. In June 1857 he married Harriet Bartlett, daughter of his chief in the Department of Philosophy. They had five children, John (1858-1868); William, (1860-1906), a Major in the Army; Henry (1862-1862); Mary Campbell, born 1865; and Richmond or Richard, born 1865, a Major in the Army.

While on leave in 1860–1861, Schofield was Professor of Physics at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, until the Civil War began.

He served throughout the Civil War in command positions, receiving the Medal of Honor for heroism in battle. When the Civil War broke out, Schofield became a Major in a Missouri Volunteer Regiment and served as Chief of Staff to Major General Nathaniel Lyon until Lyon's death during the Battle of Wilson's Creek in August 1861.

At Wilson's Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, in his first wartime engagement Schofield and others advised General Lyon to retreat in the face of overwhelming odds, but his advice was not considered, resulting in a Union loss of 258 dead and more than 1300 total casualties. The Union had 5400 men; the Confederates 10,175.

Lyon's regiment charged, with him at the head. As is often the case in hand to hand combat, confused fighting took place at this point, and clearly, neither side had a clear advantage. The Confederates far outnumbered the Federals, but Union troops held a better position and had more artillery.

At

about 10 a.m., the Confederates killed General Lyon's horse and wounded

the general in the head and leg.

At

about 10 a.m., the Confederates killed General Lyon's horse and wounded

the general in the head and leg.

Lyon then walked a short distance to the rear and had his head wound bound. He got another horse, rallied some troops, and was leading them forward when he was shot through the heart, fell to the ground, and died immediately (depiction at right). He was the first Union General Killed in Action in the Civil War.

Schofield then led a successful charge. The engagement was then considered as one of the severest of the Civil War. "Never before considering the number engaged had so bloody a battle been fought on American soil; seldom has a bloodier one been fought on any modern field." The Confederate forces lost 278 dead and more than 1200 total casualties. It was the bloodiest battle yet in the Civil War. The public was shocked and outraged. But battles were to get much worse, and much more bloody.

Schofield "was conspicuously gallant in leading a regiment in a successful charge against the enemy," according to the Medal of Honor Citation he received on July 2, 1892. Schofield was one of five soldiers who won the Medal of Honor at Wilson's Creek.

Schofield was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers on November 21, 1861, and to Major General of the Army of the Frontier in Missouri operations on November 29, 1862.

On

April 17, 1863, he took command of a division in the XIV Corps of the

Army of the Cumberland.

On

April 17, 1863, he took command of a division in the XIV Corps of the

Army of the Cumberland.

In 1864, as Commander of the Army of the Ohio, Schofield took part in the Atlanta Campaign under Major General William T. Sherman. Sherman, after the fall of Atlanta, took the majority of his forces on the March to the Sea through Georgia.

Schofield's Army of the Ohio was detached to join Major General George H. Thomas in Tennessee. Confederate General John Bell Hood invaded Tennessee, and on November 30, 1864, Hood attacked Schofield's smaller Army of the Ohio in the Battle of Franklin. Schofield successfully fought off Hood and joined his forces with Thomas. For defeating Hood's larger army at the Battle of Franklin, Schofield was awarded the rank of Brigadier General in the Regular Army on November 30, 1864.

On December 15-16, 1864, Schofield led his Army of the Ohio to victory at the Battle of Nashville.

Ordered to operate with Sherman in North Carolina, Schofield moved his entire 15,000 man army with artillery and baggage 1800 miles by rail and sea to Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in only 17 days, occupied Wilmington on February 22, 1865, fought the action at Kinston on March 10, and was awarded the brevet rank of Major General on March 13, 1865.

On March 23, Schofield joined Sherman at Goldsboro. He was present at the surrender of Johnston's army on April 26, and was charged with the execution of the details of the capitulation.

After the war, Schofield was sent on a special diplomatic mission to France in 1865-1866, because of the presence of French troops in Mexico.

During Reconstruction, Schofield was appointed by President Andrew Johnson to serve as military governor of Virginia. He commanded the Department of the Potomac in 1867.

He served as Secretary of War in the cabinet of President Andrew Johnson from June 1, 1868 until the end of Johnson's term on March 13, 1869.

In

1873, Schofield was given a secret task by Secretary of War William Belknap

to investigate the strategic potential of a United States presence in

the Hawaiian Islands. Schofield recommended that the United States establish

a naval port at Pearl Harbor.

In

1873, Schofield was given a secret task by Secretary of War William Belknap

to investigate the strategic potential of a United States presence in

the Hawaiian Islands. Schofield recommended that the United States establish

a naval port at Pearl Harbor.

From 1876 to 1881 he was Superintendent at West Point. After serving in various departments throughout the country, he succeeded to command of the entire Army on the death of Lieutenant General Philip S. Sheridan (who graduated in the same class with Schofield at West Point in 1853), and served as Commander of the Army from August 14, 1888, until his retirement.

His wife, Harriet Bartlett Schofield, died December 24, 1888, in Washington D.C., at the age of 55. John married Georgia Kilbourne in 1891. On April 4, 1897, they had a daughter, Georgia.

He was a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion in the United States.

On February 5, 1895, Schofield was promoted to Lieutenant General.

Lieutenant

General John McAllister Schofield, United States Army, was forcibly retired

for age on his 64th birthday on September 29, 1895. His memoirs, Forty-six

Years in the Army, were published in 1897.

Lieutenant

General John McAllister Schofield, United States Army, was forcibly retired

for age on his 64th birthday on September 29, 1895. His memoirs, Forty-six

Years in the Army, were published in 1897.

He is

memorialized by the military installation Schofield Barracks, Hawaii.

Schofield Barracks occupies 17,725 acres on central Oahu. The base was

established in 1908 to provide defense for Pearl Harbor and the Hawaiian

Islands. It has been the home of the U.S. Army's 25th Infantry, known

as the Tropic Lightning Division, since 1941. As of the 2000 Census, the

barracks population was 14,428 military personnel and families.

Prior to his death, he was the last surviving member of Andrew Johnson's Cabinet.

John M. Schofield died in Saint Augustine, Florida, on March 4, 1906, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

His brother, Charles Brewster Schofield, a Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Cavalry, long served as his Aide-de-Camp, and is also buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

His son-in-law, Avery Delano Andrews (1864-1959), Brigadier General, United States Army, and his daughter Mary Campbell Schofield Andrews are also buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Daughter Mary (1865-1945), married Andrews on September 27, 1888. They had two children, Scofield (1889-1971) and Delano (1894-1959).

Today, John Schofield is remembered for a lengthy quotation that all cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point and the United States Air Force Academy are required to memorize:

George

Wheeler Schofield, John's younger brother, was born in Gerry, New

York, on September 30, 1833, and was just 10 when the family moved to

Freeport, Illinois. He rose to General in the Civil War, was a respected

"Buffalo Soldier," designed the Schofield Revolver and was commander

of Fort Apache.

George

Wheeler Schofield, John's younger brother, was born in Gerry, New

York, on September 30, 1833, and was just 10 when the family moved to

Freeport, Illinois. He rose to General in the Civil War, was a respected

"Buffalo Soldier," designed the Schofield Revolver and was commander

of Fort Apache.

He enlisted in the 1st Missouri Volunteer Infantry in November 1861 and served with his brother John who was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers on November 21, 1861.

George was a Captain in Company A, 1st Missouri Light Artillery at the Siege of Vicksburg, Tennessee.

He earned a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in the 2nd Regiment Missouri Volunteer Light Artillery. In command of the 2nd, he was active in the campaigns of Georgia.

Near the end of the Civil War, he was brevetted Brigadier General of U.S. Volunteers on January 26, 1865 for gallant and meritorious service during the campaigns in Georgia and Tennessee. The Schofield family now had two brothers who were Civil War generals!

After the Civil War he chose to remain in the army and was given the rank of Major in the 10th Cavalry formed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1866. Cheyenne warriors gave the 10th Cavalry the nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" out of respect for their fierce fighting in 1867. The literal translation was "Wild Buffaloes." The 10th Cavalry had several companies of Negro soldiers. Eventually all Negro soldiers were called Buffaloes or Buffalo Soldiers.

George participated in campaigns against the Cheyennes, Arapahos and Comanches in the Indian Wars. On October 25, 1874, troops under command of Major Schofield pursued Comanches near Elk Creek and captured "68 warriors, 276 squaws and children, and about 1500 ponies." The prisoners were taken to Fort Marion, Florida, under charge of Captain Pratt, who earned distinction for educating Indians as Superintendent of the Carlisle Indian School.

Schofield was assigned

to Fort McKavett (west of San Antonio, Texas) with the 24th and 41st

Infantry Regiments. He came up with a better design for army pistols,

and worked with Smith and Wesson Firearms to manufacture his design.

He

patented several modifications to make it easier to reload on horseback

while holding the reins. In 1875, Schofield submitted his design to

the Ordnance Board. It was adopted as a substitute standard. The .45

caliber Smith & Wesson Schofield Revolver (at right) was named for

him in 1875.

He

patented several modifications to make it easier to reload on horseback

while holding the reins. In 1875, Schofield submitted his design to

the Ordnance Board. It was adopted as a substitute standard. The .45

caliber Smith & Wesson Schofield Revolver (at right) was named for

him in 1875.

Cavalrymen preferred the Schofield Pistol over the Colt Model 1873 because with it’s break-top design, it was far faster to reload, especially on horseback. From 1875-1878, the army purchased 5,000 Schofields (out of 9,000 manufactured), but eventually dropped the design. Buffalo Bill Cody, Virgil Earp, Pat Garrett, John Wesley Hardin, Frank and Jesse James, Cole and Jim Younger and many others used the Schofield.

In 1876, George Schofield married Alma V. Bullock at Fort Concho, Texas.

In 1879, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the 6th Cavalry and led relief troops at the Battle of Cibicu, during the Apache Wars.

Schofield's last duty was as post commander of Fort Apache, Arizona. The 1948 movie Fort Apache, directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne and Henry Fonda is about the fort when Schofield was commander, but the movie is entirely fiction and mixes facts.

In 1882, he began suffering from severe headaches. He went to The Presidio in San Francisco and was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. He took one of his own Schofield Pistols and shot himself in the right eye.

Lieutenand Colonel George Wheeler Schofield died Dec. 17, 1882, age 49, and is buried on the grounds at Fort Apache, Arizona.

This

is one of the earliest photos I have found of Freeport. This is the

original Emmert Drug. The building was built in 1846, but I don't

know when the photo was taken. Note the hitching posts at the front

of the sidewalk.

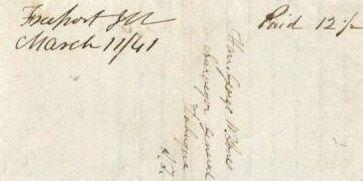

This letter was mailed from Freeport in 1841! The notation in place of postage noted that 12-1/2 cents was paid on March 11, 1841. It was mailed to the Honorable George Howe, Surveyor General, Dubuque, Iowa.

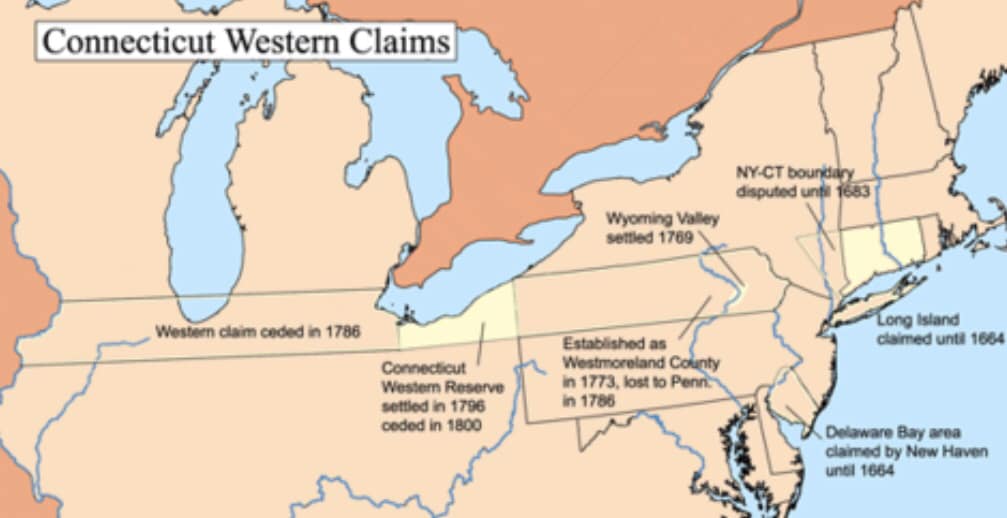

Was Freeport ever a part of Connecticut? That seems like a silly question, doesn’t it?

The colony of Connecticut, and later the State of Connecticut claimed as its state borders all land from 41 degrees to 42 degrees 2 minutes north latitude, a distance of 120 miles, from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

They relinquished most of the claims in 1786, and didn’t give up a portion in Ohio until 1800.

Freeport is located at 42 degrees, 17 minutes north, so the answer is no, Freeport was never a part of Connecticut.

But where is the line 42 degrees 2 minutes? It actually forms the southern border of Stephenson County, so no part of the county was ever in Connecticut.

But Baileyville, Forreston, Mt. Carroll, Lanark and all of Chicago were in Connecticut!

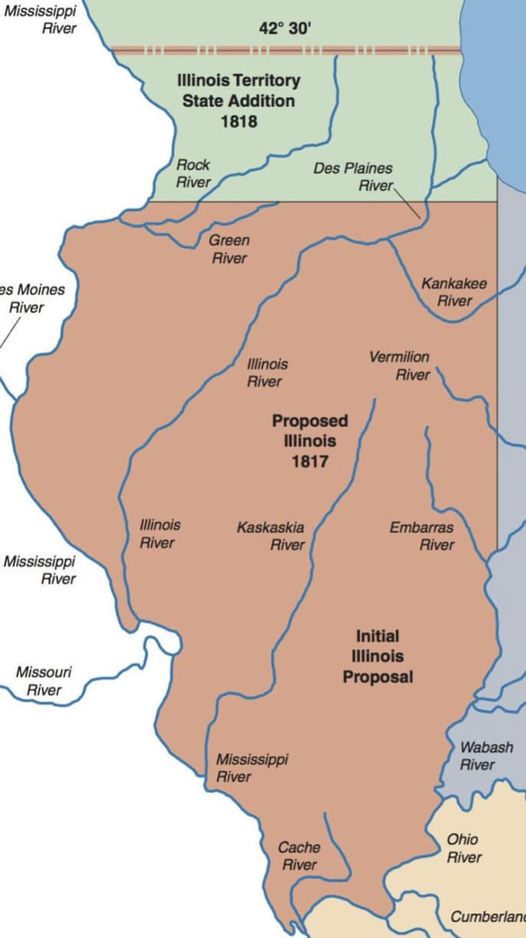

Freeport, Wisconsin?

Did you know that at two different times in history that Freeport almost became a part of Wisconsin?

In the early 1800s there was the great rivalry between the free states and the slave states. Every time the south created a new slave state, the north would carve out territory to create a free state to maintain a balance of power in Washington.

In 1817,

Mississippi was admitted to the union as a slave state, so the north wanted

to create Illinois. The western border of Indiana would become the eastern

border of Illinois, the Ohio River was the natural southern border, and

the Mississippi River would form the western border. The only question

was where the northern border should be.

The southern tip of Lake Michigan was proposed to be the starting point,

with the line going straight west. This would have put Freeport well into

Wisconsin.

Some were concerned, even as early as 1818, that if civil war was to break out, that the Mississippi River trade route could be closed off. So a proposal was made to move the northern border of Illinois to 42 degrees 30 minutes north latitude so that a port could be created in Chicago on Lake Michigan. This was the proposal that passed. About 8500 square miles, 5.5 million acres, were taken from the Wisconsin territory, and Freeport, 17 years before it was founded, went from the Wisconsin territory to the State of Illinois.

By 1840, just five years after Freeport was founded, the people in Northern Illinois felt apart from the politics of Southern Illinois, and wanted to join Wisconsin. So, between 1840-1842, there was a move to secede from Illinois.

Secession would require all 14 counties affected to vote for secession, approval from both the legislatures of the State of Illinois and the Territory of Wisconsin, plus approval of the United States Congress.

In the end, only the people in the counties of Jo Daviess, Stephenson and Boone voted to secede from Illinois and join the Wisconsin Territory (Wisconsin didn’t become a state until 1848). If secession succeeded, Freeport would then be in Wisconsin.

The Illinois legislature would never have approved: both the Chicago financial district and the Galena lead mines were too valuable to the Illinois economy.

In Stephenson County 570 votes were recorded at the election: the total was 569 in favor to one opposed to secession!

But the will of the people of the other 11 counties prevailed and Freeport remained in Illinois.

Click

on any year in the chart below to see the class and other info,

such as postcards, people and events from that year.

|

1850

|

|||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

2024

|

2025

|

2026

|

2027

|

2028

|

2029

|

|

2030

|

2031

|

2032

|

2033

|

2034

|

2035

|

2036

|

2037

|

2038

|

2039

|

|

2040

|

2041

|

2042

|

2043

|

2044

|

2045

|

2046

|

2047

|

2048

|

2049

|